Trollope, Z and kauri gum

17th Feb 2025 - Blog

Every now and again you need to go back and read a Trollope book or two. They are unexcelled for

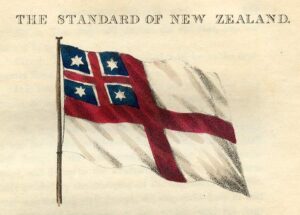

The New Zealand flag flying in China in 1834

Indicative of temerity and thoughtlessness

At the end of a short book on China, and particularly on the activities of the East India Company trading out of Canton, published in London in 1834 by Peter Auber, Secretary of the Company in London, there is a page or two that brings the New Zealand reader up short.[1] He gives an account of a piratical conspiracy by some British and American sailors out of a job in Macau, ’…the object of which was to seize upon the company’s cutter, and carry her off to the north-east coast of China, with the intention of plundering Chinese junks, and seizing the John Bigger, a British vessel employed there as an opium-receiving ship.’ The conspirators were found out, and the ringleader was ‘a person named Henry Steele, lately second mate of a ship called Sir George Murray sailing under the New Zealand flag, with a pass from New South Wales.’

The date of the incident appears to be May 1833. Auber says: ‘By advices received on the 10th of this month (January 1834), from Macau, dated in May last…’ and later ‘..The last advices from China are dated at the close of June 1833.’ Auber is writing in London, and the Company received the last communication that he includes in his book, in January 1834, sent from Canton in June 1833. So it appears that the incident occurred in May 1833, and there was a ship the Sir George Murray flying the New Zealand flag. But in 1833, there was no New Zealand flag, although the same ship was coincidentally earlier involved in demonstrating the need for one. The dates don’t quite add up, but there is a story here.

In 1830, a trader, the Sir George Murray, was built in a shipyard at Horeke on the Hokianga established after the Ngāpuhi chief Patuone had visited Sydney in 1826, hoping to encourage trade with the Hokianga, a shorter route than around to the east coast anchorage at the Bay of Islands. At 394 tons, the trader was the largest built there at the time. It was built in partnership with Thomas Raine and Gordon Brown of Sydney, and co-owned by Patuone and his relative Te Taonui. Later that year it was seized in Sydney, as most historians will have it, since it did not fly a national flag, there not being one for New Zealand at the time. The story is that the Rangatira hoisted a Māori cloak to indicate the ship’s nationality. There is some dispute however, over the reasons for the seizing of the ship. It may equally have been due to Raine’s bankruptcy.[2] A contemporary notice in The Australian, November 26 1830, supports the lack of flag as the reason, giving the owners a good telling off: ‘Immediately upon her reaching this part from New Zealand on Thursday evening, The Sir George Murray…..was seized by the Customs and is now detained in Neutral Bay, with a valuable cargo on board, consisting of timber and flax, for a breach of the navigation laws, for sailing without a Register……and it is no less strange than pitiable, that the enterprising owners do not endeavour to learn how far they could secure themselves in the fruits of their industry before engaging in the toil, and incurring the expenses of a work at once so creditable to the nautical skill and Mercantile spirit of Australia: yet under present circumstances, so completely indicative of temerity and thoughtlessness.’[3]

A couple of years later another ship was seized, at last prompting the British Resident in New Zealand, James Busby, to go about providing a national flag. Three designs were made by the missionary Henry Williams, the NSW Governor had them sewn up, and they were sent over to Waitangi on the HMS Alligator in March 1834 for the local chiefs to choose from. The favoured design received 12 out of 25 votes and was adopted, becoming known as the United Tribes’ flag, or Te Kara (the colours).[4]

It wasn’t quite such a convivial process as has been explained in some histories. The surgeon on HMS Alligator, William Marshall has left an eye-witness account.[5] On March 20th, 1834, ‘…three different designs were brought hither in the Alligator, for the chiefs to select one, and to-day was fixed for the occasion. A considerable number of the natives were met at the Residency, including about thirty of the Tangata Mauri, or heads of tribes, and the spectacle might have been rendered an imposing one but for the attempt to separate between the noblesse and the canaille of New Zealand, by confining the choice of the flag to the former, and excluding altogether the latter from taking part in the affair. As it was, the great body of the chiefs assembled in a large oblong-square tent, screened in on one side by canvas, and canopied by different flags; this was divided into two lesser squares by a barricade across the centre, and the Tangata Mauri were called out of the one square into the other, according to their respective ranks, and to the no small discontent of the excluded. Mr Busby made a speech….and the votes of the electors were taken down by Hongi.’ One of the chiefs asked Marshall for his opinion and then voted accordingly. Two declined to vote at all, in fear of there being some nefarious design behind it all. In other words, it was rigged towards the preferences of a few chiefs, and not everyone was happy. Nevertheless, the chosen flag was hoisted and the Alligator gave a 21 gun salute. The flag continued to be used for many years. The current New Zealand flag didn’t appear until 1869 and was not formally adopted until 1902, the Union Jack being the recognised ‘national’ flag for some 60 years after Te Tiritiri. The United Tribes flag is also illustrated in the Rev William Yate’s book on New Zealand of 1835.[6]

So what was the Sir Henry Murray doing in Macau in 1834? In 1831, it was sold at auction in Sydney to Captain Thomas MacDonnell and continued trading between Sydney and the Hokianga in that year, Patuone and Te Taonui endorsing the sale and giving MacDonnell the privileges of a chief.[7] The ship’s movements between 1831 and 1834 are presumably somewhere recorded in notices of sailings and arrivals in Australian ports, but are not immediately visible. There was frequent trade between Australia and China at the time, ships returning from Australasia to England also sometimes took a route that included China, a centre of growing trade of tea, porcelain and other Chinese good for England, as well as the opium trade with India. There was no official Australian or New South Wales flag flown on ships at the time, the Union Jack and Red Ensign of Britian being used. However, there was a New South Wales merchants’ flag designed by Sydney’s Harbour Master, Captain John Nicholson. It is not too unlike (well most empire flags of the day had the same components) the eventual United Tribes’ flag, and was unofficially used by NSW traders in the 1830s. It was banned in 1883.

So what was the Sir Henry Murray doing in Macau in 1834? In 1831, it was sold at auction in Sydney to Captain Thomas MacDonnell and continued trading between Sydney and the Hokianga in that year, Patuone and Te Taonui endorsing the sale and giving MacDonnell the privileges of a chief.[7] The ship’s movements between 1831 and 1834 are presumably somewhere recorded in notices of sailings and arrivals in Australian ports, but are not immediately visible. There was frequent trade between Australia and China at the time, ships returning from Australasia to England also sometimes took a route that included China, a centre of growing trade of tea, porcelain and other Chinese good for England, as well as the opium trade with India. There was no official Australian or New South Wales flag flown on ships at the time, the Union Jack and Red Ensign of Britian being used. However, there was a New South Wales merchants’ flag designed by Sydney’s Harbour Master, Captain John Nicholson. It is not too unlike (well most empire flags of the day had the same components) the eventual United Tribes’ flag, and was unofficially used by NSW traders in the 1830s. It was banned in 1883.

What more do we know of the Macau incident in May 1833? The information was mostly provided by a sailor David Brown, sitting in a Macau jail for being drunk and disorderly. He said that the British seaman Henry Steele, as second officer on board the Sir George Murray, had arrived very recently, and on landing had approached others to conspire to size a boat, the H C Cutter[8], and then head up the coast plundering. Brown was approached to join, eventually agreed, but got cold feet the next morning. Eventually the plot was exposed, the men involved arrested, and the Select Committee (the administrative body of the East India Company in Canton) asked the Portuguese authorities to detain Steele so he could be extradited to England, They agreed and Steele was shipped off to Singapore in the first instance. It’s not clear what happened to Steele after that.[9] You can read more on Auber’s book and on the eccentric Sinophile Thomas Manning here (read more).

So we are left with a ship that was built in the Hokianga, involved in an issue of lack of national registration, that eventually ended in the United Tribes’ flag, still to been seen flying these days, and then the problem of a New Zealand flag flying on the same ship in May 1833, before the United Tribes’ flag was born. Perhaps it was the New South Wales merchant flag, since it is likely the ship came up from Australia to trade. Auber, sitting in London, could have got the nationality wrong. In the end it doesn’t matter. It’s just nice to have the mind piqued by little details that show how connected things were even in those rough and ready days.

[1] Auber, Peter. China. An Outline of its Government, Laws, and Policy, and of the British and Foreign Embassies to, and intercourse with, that Empire. London: Parbury, Allen, and Co., 1834.

[2] Bevan-Smith. Corralling Consent: An inquiry into the mythical beginning of the New Zealand flag. 2016.

[3] The Australian, Friday 26 November 1830, p.3

[4] United Tribes flag, URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/politics/flags-of-new-zealand/united-tribes-flag. (Manatū Taonga — Ministry for Culture and Heritage)

[5] Marshall, W.B. A personal narrative of two visits to New Zealand in His Majesty’s ship Alligator, A.D. 1834. London: James Nisbet and Co, Berners Street MDCCCXXXVI [1836]. pp 107-109.

[6] Yate, W. An account of New Zealand; and of the formation and progress of the Church Missionary Society’s mission in the Northern Island. London: Seeley and Burnside. MDCCCXXXV (1835). p. 22.

[7] http://www.patuone.com/files_life/commerce.html

[8] Probably not the boat’s name, but referring to a Hong Kong cutter, although Hong Kong was yet to become a British possession resulting from the Nanking Treaty of 1842.

[9] Karsh, Jason The Root of the Opium War: Mismanagement in the Aftermath of the British East India Company’s Loss of its Monopoly in 1834.University of Pennsylvania, PhD Thesis, 2008. Pp 34-38.

https://repository.upenn.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/3d6113d2-1f6f-43a3-ac65-3c91309fb418/content

17th Feb 2025 - Blog

Every now and again you need to go back and read a Trollope book or two. They are unexcelled for

3rd Jan 2023 - Rare and Early Books

Early books on China: Over the 17th and 18th centuries, some hundreds of missionary priests made the hazardous voyage to