Trollope, Z and kauri gum

17th Feb 2025 - Blog

Every now and again you need to go back and read a Trollope book or two. They are unexcelled for

When you read early literature, you frequently come across things you would like to share.

The personalities of those who wrote early accounts of travel and settlement in New Zealand often shine through their writings. Characters, such as Frederick Maning and Jerningham Wakefield, easily come to the fore, and others, like Bishop Selwyn, are helped by the many references and commentaries on them by other writers. However, many are often hidden behind their words and observations and it is often in the little asides, incidents, vignettes, in early accounts, that we see something a bit different in the personalities of the authors. They provide a glimpse of early life, and shine a light beam on things that we might encounter or recognise in ourselves.[1]

Rongoā

New Zealand’s first Anglican bishop, George Augustus Selwyn was ordained and appointed to the bishopric in 1841 in England, within a week of his brother turning it down, and landed at Auckland in May 1842. Its hard to find a negative word written about Selwyn, widely liked and admired, and he certainly made sure that everyone had the chance to form an opinion. His some 15 years in New Zealand were marked by his extensive travel across much of the country, often in rough conditions, visiting missions, settlers and settlements, towns, and Māori leaders, pas and maraes. In his first 6 months he travelled deep into the North Island, and his account is lively; Selwyn is in command, preaching, walking, opening schools, and then in the middle of some rough and wet country, we find him making hot chocolate[2].

‘The men being very tired, I made them my usual restorative, which I call ‘rongoa’ (medicine), as it is inconsistent with native etiquette for a Chief to prepare food. My Rongoa is made thus – Boil a large kettle of water: in a separate pan, mix half a pound of chocolate beaten fine, two pounds of flour, and half a pound of sugar; mix to a thin paste, and pour it into the water when boiling; stir till the mess thickens. This is a most popular prescription with the natives, as you might judge from the ingredients, and very nourishing and warm for men who have to sleep out at night in a damp climate.’

You can see the attraction of the concoction when you are wet and cold, but you would like to think that there were blankets and tents enough for everyone.

The lotus-eaters

The long voyage out to New Zealand was a testing time for some, one of survival for many in steerage, but for the better off, one of languor, educational opportunities, refined reading, boredom, and the contrivance of entertainments and any activity that would pass the time.

Hypnosis

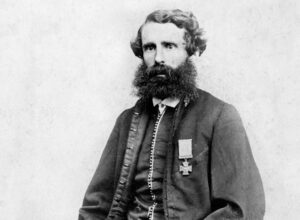

In 1839, the Tory was sent out from England by the NZ Company, in a pre-emptive strike, getting ahead of any Government regulation of immigration, to start finding suitable sites for settlements and buy land. On board was Edward Gibbon Wakefield’s brother Col. William Wakefield, the former’s wayward 19-year-old son Edward Jerningham, the Company’s naturalist Ernst Dieffenbach, and it’s 18-year-old draftsman Charles Heaphy (see photo).[3] They filled their time issuing a weekly paper, learning te reo Māori, shooting seabirds, and running a debating society. Heaphy suggested a debate on the French revolution, which was not all that far in the past, but it was Jerningham Wakefield who you might have enjoyed more. He twice put Heaphy under hypnosis. Col. William Wakefield recorded it in his journal. It seems that Heaphy had a rather violent reaction to it, but that didn’t stop Jerningham from repeating the entertainment a few days later, when it had ‘Nearly the same effect as before’, according to Uncle William.[4] Jerningham later entered politics, and with a great weakness for alcohol, was locked in a room with fellow MPs by the Chief Whip so that they might later, sober, vote appropriately. The story goes that opposition MPs lowered a bottle of whiskey down the chimney.[5]

Game of stones

And then there were games. Charles Warren Adams, 18 years old, sailed out in 1851, stayed 10 weeks and returned with enough material to write a book[6]. His voyage was one where ‘all on board have fallen into the regular lounging, dreamy, lotus-eating sort of existence which characterises life during a long voyage’ – well, for the cabin passengers at least. There wouldn’t be much lotus eating in steerage. The cabin passengers also ran a weekly newspaper, called the ‘Sea Pie’, which only lasted 4 weeks as languor, or a lack of material, set in. They put on theatricals, and played an ‘ancient Egyptian game, which we named Sesostris. It was played by two persons, on a board placed between them, having twelve small hollows, six on each side. Six tamarind stones were placed in each of these holes. The first player, taking up the contents of one of the holes, dropped them one by one into the others, and, taking up the contents of the hole into which the last stone fell, he proceeded as before, and continued the process until the last stone fell into an empty hole….’ It is a long explanation that is best read in the book. ‘Monotonous and unintellectual as this game undoubtedly is, it helped us while away many a weary hour.’

Cabin class

Another lotus-eater, the well-off Scotsman Alexander Marjoribanks, landed in Port Nicholson in February 1839 as one of the New Zealand Company’s first immigrants, but stayed less than a year, also enough time to provide material for a book[7]. He was a life-long traveller, so knew what he was about in cabin class: ‘…we, who were in the cabin,….…fared sumptuously every day; a circumstance highly creditable not only to the New Zealand Company, but to the liberal captain of the ship. In fact it may be said that we did little else but eat, drink and sleep during the voyage. We had four meals per day, and at dinner had always five or six dishes of fresh meat, with a carte blanche of claret and other wines, besides a dessert of fruit.’[1] He numbers the pigs, sheep and head of poultry on board, and married 22 year old Ann Forbes when off the coast of South America, on December 25. He doesn’t seem to have been aware that his ‘liberal captain’ (John Hemery) was at the same time holding back food from the folks below. On 14 March, 1840, 29 steerage passengers, now landed in Port Nicholson, signed a letter of complaint to the New Zealand Company about rations (which are itemised and would have been part of the agreement regarding their passage) being held back from them by the captain during their four and a half month voyage.[8]

Premium economy

On some ships there was an intermediate class, not a cabin to oneself or with family, nor steerage, but a shared cabin, we might call it premium economy. Another single young man, Edwin Hodder at 20 years old, arrived in Nelson in 1857. ‘One cabin was set apart for single men, and into this I was consigned with three others. We sat down that night on our boxes, which were jammed together on the floor of the cabin, a compartment eight feet by six feet, containing four berths like coffins, just wide enough to lie in without turning, and talked over the prospects before us. To me they presented no very agreeable aspect. Our cabin was about the most uncomfortable in the whole ship; it was totally dark when the door was closed, even on the brightest days.’

But single, bored men will make their own entertainment. ’In the second cabin was an ancient maid ofthe dubious age of thirty or thereabouts, rejoicing in the name of Amelia.’ This Amelia drew the attention of ‘a young man who was going to New Zealand, for the simple reason that his society was not required at home. He was what is termed in the colonies “cranky”; that is, possessed of an unusually small modicum of brains, and having a strong tendency to imbecility. He had not an imposing appearance, being diminutive in stature and possessing a most insinuating cast in one eye, which always seemed struggling to look round the corner. But with this identical eye he spied out Miss Amelia soon after leaving England, and whether he fascinated her, or the eye was evil, is not known .’ Amelia seemed attracted, despite the flaws, so Hodder and his mates contrived a letter to be written to the ‘cranky’ young man, purporting to be from Amelia and suggesting an assignation. They dressed another fellow in woman’s clothing, and the assignation, as planned, didn’t go well, with the youth proposing to the fake Amelia, who boxed his ears and sent him sprawling.

Nothing venture, nothing have

Edwin Hodder gives the air of a young man out for a bit of adventure, wanting to try new things. Like gold mining. There is word of gold in the Aorere valley, about 100 or so miles, as it was then, west of Nelson in Golden Bay, then known as Massacre Bay. ‘Nothing venture , nothing have’ he says, and buys some canvases and stitches together a tent. He cant find any companions to go with him. ‘My dear fellow, don’t think of such a thing. Nature never cut you out for a gold,’ they said, and he resolves to go alone. ‘I could not divest myself of a strange uncomfortable feeling, half of shame, half of pride, as I started off through the town with my tent, blankets and provisions on my back, and a spade, pick and shovel over my shoulder, attired in a blue slop, corduroy trousers, water-tight boots, and a felt cap.’ After landing by ship at the mouth of the Aorere river, he sets out for the diggings, with some new mates: ‘one was a German who could not speak English, and had a club-foot, which did not, however, interfere with his digging; another was a German who spoke English, and acted as interpreter; the third was an old colonist, whose weakest points, as I afterwards found, were brandy and tobacco.’ They find very little gold, and eventually Hodder decides to walk the hundred miles and sets off alone: ‘in four days [I] arrived at home, after an absence of six weeks, worn out with fatigue, clothes torn and tattered, and money spent. The two shillings and three pence I first earned, still hung from my neck, and to this day it is suspended on a wall in my room, in a neat little frame, where it seems to say, “Depend upon it , city clerks [Hodder later became a civil servant in London], ye are not cut out for gold-diggers.”

It is a memorable picture of a young man, inexperienced, marching out of town all togged up in new gold mining gear, a bit embarrassed but with a touch of pride. Edwin Hodder eventually spent four years in New Zealand, wrote his travel account[9] when back in London, and later went on to write hymns.

[1] These vignettes come from the longer accounts of early books and their writers on my website https://www.ianferg.nz

[2] Selwyn, G.A. New Zealand. Part 1. Letters from the Bishop to the Society for the propagation of the Gospel, together with extracts from his Visitation journal, from July 1842 to January 1843. London: Printed for The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel: Sold by Rivingtons, Burns, Hatchard and Sharpe. 1847. pp. 79-80.

[3] Heaphy, C. Narrative of a residence in various parts of New Zealand. Together with a description of the present state of the Company’s settlements. London, Smith, Elder and Co., 65, Cornhill. 1842. Wakefield, E.J. Adventure in New Zealand, from 1839 to 1844; with some account of the beginning of the British colonization of the islands. In two volumes. London: John Murray,

[4] Edwards, D. E., The voyage of the “Tory”: birth of Wellington: Colonel Wakefield’s preliminary arrangements for the settlement of the city. The New Zealand Railways Magazine, vol. 15, issue 3 (June 1, 1940); Bloomfield, P., Edward Gibbon Wakefield, builder of the British Commonwealth. London, Longmans, 1961 p.213;

[5] ‘The Opposition’, URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/politics/house-of-representatives/opposition, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 15-Jul-2014. Accessed 15 November 2022

[6] Adams, C.W. A spring in the Canterbury Settlement, by C. Warren Adams, Esq. with engravings. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. 1853.

[7] Marjoribanks A Travels in New Zealand, with a map of the country. London: Smith, Elder and Co. MDCCCXLVI

[8] New Zealand Company: Letter from steerage passengers on the Bengal Merchant to Samuel Revans. Ref: fMS-Papers-12194. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/37973543. Accessed 26 August 2022.

[9] Hodder, E. Memories of New Zealand life. London: Longman Green, Longman & Roberts. 1862.

17th Feb 2025 - Blog

Every now and again you need to go back and read a Trollope book or two. They are unexcelled for

11th Dec 2022 - Reading and writing

Whilst translating Johann Christian Hüttner’s account of the Macartney Embassy to Peking in the 1790s, (more info). I came across