Trollope, Z and kauri gum

17th Feb 2025 - Blog

Every now and again you need to go back and read a Trollope book or two. They are unexcelled for

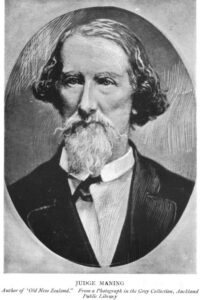

Frederick Edward Maning leaves you rather breathless. A tall, rangy Irishman, he arrived in the Hokianga in 1833 from Hobart, got into business, fathered a child, married a high-born Māori woman, fought with Māori, spoke against the Treaty, was called ‘a double faced sneaking thief‘ by a contemporary settler, Edward Markham, wrote some books on early New Zealand, particularly Heke’s war, taking up his well-cultivated persona of a ’Pakeha Māori’, and ended up as judge of the Land Court. His books can be long-winded, discursive, pretty much how he may have spoken, but often acute, amusing, and providing a usually accurate view of the times.[1]

In his best known book, Old New Zealand[2], he recounts his arrival and early days in the new colony. He arrives in the Hokianga, and then takes two chapters to get ashore. But its worth waiting for. He dressed himself for the occasion: ‘For the honour and glory of the British nation, of which I considered myself in some degree a representative on this momentous occasion, I had dressed myself in one of my best suits. My frock-coat was, I fancy, “the thing;” my waistcoat was the result of much and deep thought, in cut, colour, and material; I may venture to affirm that the like had not been often seen in the southern hemisphere. ….. My hat looked down criticism, and my whole turn-out was such as I calculated would “astonish the natives,” and create awe and respect for myself individually and the British nation in general; of whom I thought fit to consider myself no bad sample’. He transfers to a small boat: ‘The boat darts on; she touches the edge of a steep rock; the “haere mai” has subsided; six or seven “personages”—the magnates of the tribe—come gravely to the front to meet me as I land. There are about six or seven yards of shallow water to be crossed between the boat and where they stand. A stout fellow rushes to the boat’s nose, and “shows a back,”….’ The young Māori man waded out and Maning tightens his hat and buttons his coat and climbs onto the offered shoulders. His bearer takes one step, slips and down they go ‘backwards, and headlong to the depths below’, to the delight of the crowd on the shore, who seem more interested in his hat: ‘The whole tribe of natives had followed our drift along the shore, shouting and gesticulating, and some were launching a large canoe, evidently bent on saving the hat, on which all eyes were turned.’ Maning succumbs: ‘ The furies take possession of me! I dart upon him like a hungry shark!’ He fails to drown the fellow and they swim to shore, where there are delighted cries of utu, and there is only one thing to do.

In his best known book, Old New Zealand[2], he recounts his arrival and early days in the new colony. He arrives in the Hokianga, and then takes two chapters to get ashore. But its worth waiting for. He dressed himself for the occasion: ‘For the honour and glory of the British nation, of which I considered myself in some degree a representative on this momentous occasion, I had dressed myself in one of my best suits. My frock-coat was, I fancy, “the thing;” my waistcoat was the result of much and deep thought, in cut, colour, and material; I may venture to affirm that the like had not been often seen in the southern hemisphere. ….. My hat looked down criticism, and my whole turn-out was such as I calculated would “astonish the natives,” and create awe and respect for myself individually and the British nation in general; of whom I thought fit to consider myself no bad sample’. He transfers to a small boat: ‘The boat darts on; she touches the edge of a steep rock; the “haere mai” has subsided; six or seven “personages”—the magnates of the tribe—come gravely to the front to meet me as I land. There are about six or seven yards of shallow water to be crossed between the boat and where they stand. A stout fellow rushes to the boat’s nose, and “shows a back,”….’ The young Māori man waded out and Maning tightens his hat and buttons his coat and climbs onto the offered shoulders. His bearer takes one step, slips and down they go ‘backwards, and headlong to the depths below’, to the delight of the crowd on the shore, who seem more interested in his hat: ‘The whole tribe of natives had followed our drift along the shore, shouting and gesticulating, and some were launching a large canoe, evidently bent on saving the hat, on which all eyes were turned.’ Maning succumbs: ‘ The furies take possession of me! I dart upon him like a hungry shark!’ He fails to drown the fellow and they swim to shore, where there are delighted cries of utu, and there is only one thing to do.

Maning seemed to have has a penchant for wrestling, and when his wet companion, who went by the name of ‘eater of melons’ cries utu and challenges him to wrestle, Maning complies. So they went at it: My antagonist was a strapping fellow of about five-and-twenty, tremendously strong, and much heavier than me. I, however, in those days actually could not be fatigued: I did not know the sensation, and I could run from morning till night. I therefore trusted to wearing him out.’ And indeed he did: ‘I saw my friend’s knees beginning to tremble. I made a great effort, administered my favourite remedy, and there lay the “Eater of Melons” prone upon the sand….I stood a victor; and, like many other conquerors, a very great loser. There I stood, minus hat, coat, and pistols; wet and mauled, and transformed very considerably for the worse since I left the ship. When my antagonist fell, the natives gave a great shout of triumph, and congratulated me in their own way with the greatest good will. I could see I had got their good opinion, though I scarcely could understand how. After sitting on the sand some time, my friend arose, and with a very graceful movement, and a smile of good-nature on his dusky countenance, he held out his hand and said in English, “How do you do?”. There can have been few arrivals as entertaining, and Maning never failed during his life in the colony to carry on the practice.

Maning seemed to have has a penchant for wrestling, and when his wet companion, who went by the name of ‘eater of melons’ cries utu and challenges him to wrestle, Maning complies. So they went at it: My antagonist was a strapping fellow of about five-and-twenty, tremendously strong, and much heavier than me. I, however, in those days actually could not be fatigued: I did not know the sensation, and I could run from morning till night. I therefore trusted to wearing him out.’ And indeed he did: ‘I saw my friend’s knees beginning to tremble. I made a great effort, administered my favourite remedy, and there lay the “Eater of Melons” prone upon the sand….I stood a victor; and, like many other conquerors, a very great loser. There I stood, minus hat, coat, and pistols; wet and mauled, and transformed very considerably for the worse since I left the ship. When my antagonist fell, the natives gave a great shout of triumph, and congratulated me in their own way with the greatest good will. I could see I had got their good opinion, though I scarcely could understand how. After sitting on the sand some time, my friend arose, and with a very graceful movement, and a smile of good-nature on his dusky countenance, he held out his hand and said in English, “How do you do?”. There can have been few arrivals as entertaining, and Maning never failed during his life in the colony to carry on the practice.

One farthing and one twentieth per word

Maning was not short of sense of humour and happy to make a joke against himself. He spent his life in a tussle of land issues, purchases, laws, rights, and eventually jurisdiction. In an early appearance to prove his land title before newly-appointed Land Commissioners, he enjoys his long-windedness: ‘…I made a very unwilling appearance at the court, and explained and defended my title to the land in an oration of four hours’ and a half duration: and which, though I was much out of practise, I flatter myself was a good specimen of English rhetoric, and …..which was listened to by the court with the greatest patience. When I concluded, and having been asked “if I had any more to say?” I saw the commissioner beginning to count my words, which had been all written I suppose in short hand, and having ascertained how many thousand I had spoken, he handed me a bill, in which I was charged by the word, for every word I had spoken, at the rate of one farthing and one twentieth per word…….For my part I have never recovered the shock. I have since that time become taciturn, and adopted a Spartan brevity when forced to speak….’, Its all bluff and exaggeration, and ‘Spartan brevity’ is not apparent in his subsequent writing.

A million trees

One young man who might have benefited from learning a little of Maning’s style, was Benjamin Heywood. A sub-minor character in New Zealand’s early literature, and about whom we know very little, Heywood arrived in New Zealand from Australia on December 4 1861 and spent six months here. He wrote his account, as they all did, and it was published on his return to England in 1863[3]. He seems to have lacked ‘juice’, with an Australian reviewer of his book enjoying himself at Heywood’s expense: ‘Mr Heywood says he was recommended to take the trip for the benefit of his health. We can readily believe him. He does not tell us what his complaint was, but if we might venture to speculate on it, we should at once say, in lay dialect, that he was suffering from some untoward absorption of the juices of his system. At any rate, we never had the pleasure of making literary acquaintance with a mind in which Bacon calls ‘moisture’ was less apparent. ……It is not often that a man could pass through the curious civilisation and the magnificent scenery that Mr Heywood must have encountered in Australia and New Zealand, with a vocabulary so dry, barren, and jejune.’[4]

The book in fact is not all that dry, although the man is, and you get the flavour of the man when he recounts visiting the Otago gold diggings: ‘…then I called at one of the tents to make my inquiries, I was invited in; several young men were there, who immediately placed spirits on the table, and kindly insisted that we should reciprocate healths. Hating spirits, I begged to be allowed to drink to their prosperity and happiness with the refreshing beverage tea, some of which also was on the table. It rather surprised me to meet with a tentful of such very respectable young men of the working classes as these seemed to be.’ But he does have an eye for a good joke. He visits Hawkes Bay: ‘The nearest bush to the town is about eight or ten miles off, across the Ngararuro river, and belongs to the Aborigines. The Native Lands Commissioner was most anxious to purchase it for the Europeans, and asked Hapuku, a warlike chief, who was part owner of it, what he would sell it for? “£1,000,000,” was the reply. “Can you count a million?” said the Commissioner. “Can you count those trees?” was the rejoinder,…..’ Well I don’t know if it was original, but it was worth finding in Heywood’s book.

[1] https://ianferg.nz/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Remote-in-Southern-Seas.-Early-NZ-books-1863.pdf

[2] [Maning, F.E.] Old New Zealand; A tale of the good old times. by a pakeha Maori. Auckland. Creighton & Scales. 1863.

[3] Heywood, BA A vacation tour of the Antipodes, through Victoria, Tasmania, New South Wales, Queensland, and New Zealand, in 1861-1862. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green. 1863.

[4] The Argus (Melbourne). Mon 6 Jul, 1863, p. 5

17th Feb 2025 - Blog

Every now and again you need to go back and read a Trollope book or two. They are unexcelled for

1st Dec 2023 - Blog

When you read early literature, you frequently come across things you would like to share. The personalities of those who