Bounceability

21st Apr 2024 - Blog

Occasionally when reading early literature, you come across a common word which seems to have a new meaning, though in

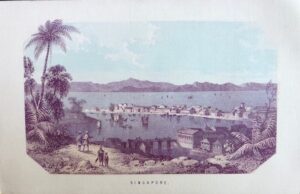

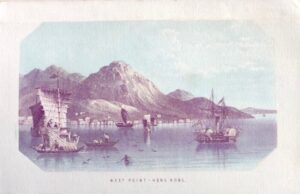

On the first trip back to China since Covid, I climbed (on the escalator) to the Mid Levels in Hong Kong to visit that estimable rare book seller Lorence, at Lokman Books. There I found a little treasure: Overland Route to India and China. T. Nelson and Sons, London. 1859. It is a small, 48 pp book in the original blue coated paper covers and describes a journey from England through the Mediterranean, across Egypt (pre-canal), India, Singapore, Hong Kong and mainland China at the treaty port of Amoy (Xiamen) and Shanghai. There is nothing especially unusual in that, except that the booklet included 12 separate chromolithograph cards showing scenes at ports on the way. The cards are two-toned in blue, and in near fine condition.

The title is initially misleading, since the journey out is not by some overland route through Russia and Siberia or Central Asia, both recognised routes, although not for the casual traveller. The overland bit is from Alexandria, through Cairo, and to Suez and the Red Sea by camel, before sailing on to Aden and then India. This route became popular around the mid-19th C, for mail and passengers, and was largely due to the development of steamships, which could navigate the shallow and often dangerous shoals of the Red Sea. In the early New Zealand travel literature, for instance, most of the early travel accounts routinely include opening chapters of the long voyage out, with its longueurs, entertainments and occasional crises. It’s a narrative of the well-off cabin passengers; we rarely hear from those below, except when the captain keeps back some of their rations to ensure the cabin folks live well.[1] Then in the 1850s, we get a glimpse of alternative routes. In Charles Hursthouse’s 2 volume account of New Zealand written for the NZ Company, there is a world map showing shipping routes that include both the Horn and Cape of Good Hope routes, along with those with the overland stretch through Panama and Suez.[2] In 1861-2, the young Benjamin Heywood, travelling for health and leisure, toured New Zealand and Australia and returned to England through Suez, now the preferred route, particularly for touring passengers.[3]

This overland route now included passages by steamer. The first steamship to sail from England to India was the Enterprise in 1825, taking the Cape route with great paddlewheels and 17 passengers.[4] However, there had been earlier suggestions of a Mediterranean-Suez route, with paddle steamers either side of the isthmus, for example as proposed by the Governor-General of India, Lord Amherst[5], in 1823. The overland Suez route was pioneered by an unreliable, possibly fraudulent character, Thomas Waghorn (1800-1850). He served in the Royal Navy in India and in the 1830s undertook the exploration of an overland route in Egypt, living among the Arabs between 1835 and 1837, and negotiating a route from Cairo to Suez. He tried to establish this as a private business, mainly for mail, but was eventually out-competed by the P&O Company in 1840. The route included resthouses, horse, donkey and camel transport and Bedouin guides.[6] From the 1840’s onwards, the overland route was the preferred route for mail and passengers, with numerous travel accounts now having a further insert of exotica with the Egyptian overland leg.[7] Trade still largely had to take the long way round, until the Suez canal opened in 1869.

There is no author given for the book, and it is published by Thomas Nelson, a publisher originating from the 18th C in Scotland, and still in existence today in various forms. There is a close relationship with the P&O shipping line, and the tract could conceivably have been published in association with them. Again, the chromolithographs are anonymous, except for one statement of acknowledgement: ‘Our views of Aden and Madras are copied, by the kind permission of the Directors of the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company that the views of Aden and Madras Company, from pictures in their possession.’ The limited palette of the lithographs, largely blue and brown, is a cost-effective way of achieving something beyond black and white, appropriate for a relatively cheap production.

This is a breezily written book, the tone set at the start: ‘Reader, our voyage is not a short one, If you consent to follow us, we will lead you from the grey skies of England, to those of the golden Mediterranean…..we will sweep you onwards to the isles of the Antipodes, hail the seaports of the far east, And rest not until we have cast out our anchor and grappled the distant shores of China!. Art thou ready for such a jaunt?’ He (we assume the author is a male) casts his eye over his 200 fellow passengers, and finds ‘military men, bronzed, quiet, gentlemanly and grave – returning to the land of their choice’, and ‘civilians – elderly men, mere bone and leather – returning to their adopted country, and ‘pleasure seekers – lovers of travel – men whose circumstances are what is conventionally termed easy, and whose time is at their disposal, and’ a few matronly partners of the before-mentioned civilians, and several blooming wives of the before-mentioned grave and bronzed military men; also one or two sickly dames, who are on their way to the genial south in search of health.’

The various ports of call are then described, their attractions, scenery and some details. If he doesn’t need to , the author doesn’t linger. Alexandria: ‘The modern city is little better than a collection of half-ruined houses and rubbish, in the midst of which are to be seen the remains of a few of its ancient palaces.’ Bombay: ‘..is very picturesque; and its beauty is doubtless enhanced in our eyes, in consequence of the endless time we have passed on the boundless ocean.’ In Hong Kong, ‘..everything that we behold is a “sight’,” and we shall find endless amusement rambling through the crowded streets where the Chinese, with shaved heads and pigtails, and clad in their loose and dirty garments, prosecute their various trades in the open air,..’. At last, Shanghai, which is the ‘ultima Thule of our voyage and British intercourse with China. Beyond this the mails proceed no further; therefore, courteous reader, we bid you farewell, and wish you an agreeable sojourn in foreign lands and a pleasant voyage home.’ This is no great travel writer, the book clearly written to attract more passengers. It ends with general information, on luggage, money, the need for a small telescope and map, and costume. Courteous reader, its best if you just look at the fine pictures.

[1] See the account of Alexander Marjoribanks (Marjoribanks A Travels in New Zealand, with a map of the country. London: Smith, Elder and Co. MDCCCXLVI.) where 29 steerage passengers complained to the NZ Company about the captain holding back some of their, itemised, provisions during their 4.5 month voyage. Marjoribanks reports how well he and his fellow cabin passengers were provided for.

[2] Hursthouse, C. New Zealand, or Zealandia, the Britain of the South. In two volumes. London: Edward Stanford, 6, Charing Cross. 1857.

[3] Heywood, BA A vacation tour of the Antipodes, through Victoria, Tasmania, New South Wales, Queensland, and New Zealand, in 1861-1862. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green. 1863..

[4] Halford L. Hoskins, The First Steam Voyage to India. Geographical Review, Vol. 16, No. 1 (Jan., 1926), pp. 108-116.

[5] The same Lord Amherst who led the failed embassy to China in 1816. Failure was no set-back to his career, and he was G-G of India from 1823 to 1828.

[6] Harcourt, F. (2004). “Waghorn, Thomas”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/28397

21st Apr 2024 - Blog

Occasionally when reading early literature, you come across a common word which seems to have a new meaning, though in

27th Feb 2023 - Blog

As you read through the early books on New Zealand (read more) the narratives of missionaries, early visitors and traders, settlers