This Extensive, Potent Empire: Overland to Peking

21st Feb 2023 - Rare and Early Books

Early books on China: Much of the literature of western accounts of travel to China focuses on the route from

William Curling Young (1815-1842) was part of a family heavily involved in colonial policy and initiatives. In the end he was the only one to follow through, only to have the adventure tragically cut short.

His father was George Frederick Young (1791-1870) MP for Tynemouth in 1832-1838, and more importantly, a New Zealand Company director. He bought land in Wellington, one a number of off-shore speculators who never visited, and had shipping interests useful to the Company. Young also wrote the agreement which emigrants on the first ship out to New Zealand signed. This turned out to be illegal and Young was embroiled in the ensuing imbroglio between Government and Company.[1] George Frederick himself was the second son, from a family of 13, of Vice-Admiral William Young (1761-1847) and his wife Anne, from a family of shipbuilders. The family firm Curling, Young & Company, established at the Limehouse Dockyard, built Indiamen and later, merchant timber steamships.[2]

William Curling Young was George’s first son, and his younger brother Frederick (1817-1913), later Sir Frederick, became chairman of the Royal Colonial Institute, manager of the shipping department of the Canterbury Association in 1848, and incidentally, coauthor of a pamphlet on New Zealand flax with Francis Dillon Bell, without ever visiting the colony. The Youngs were friends of the Wakefield’s, and their cousin was Alfred Dommett, both with large New Zealand interests and experience.

William Curling came out to Nelson on the Mary Anne in 1842. He was briefly the New Zealand Company Agent in Nelson and was offered a magistrate’s position by Governor Hobson but declined, stating that it would inhibit him from criticizing the government[3]. And then on 14 August 1842 he was drowned while crossing the Wairoa River in the Nelson region. His mother Mary gathered his letters, and a number of letters and documents are deposited in New Zealand libraries3.

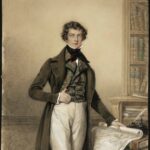

[A posthumous portrait from a family miniature of William Curling Young, standing with an open map of New Zealand. Painted by Benjamin De La Cour in 1845. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22430916]

Before he set out to New Zealand, only at the age of 25, he wrote a book. It was published In 1840, and proposed that England abandon Canton as a trading base and establish entrepôts on off-shore islands. He was critical of English policy in China, at one with his liberal stance on colonisation.

YOUNG, William Curling. The English in China. London, Smith, Elder, 1840.First edition. 12mo, xii, 142, [1](errata), folding map hand coloured in outline, publisher’s presentation binding, brown morocco, covers richly panelled in gilt, spine gilt in compartments, all edges gilt. Cordier 2362, Lust 580.

My particular copy presumably once belonged to his mother since it is inscribed on the half-title by Young: ‘To my Mother – from her dutiful & affectionate son – the Author’.

The book was written at the outset of the first opium war (1839-1842), where the Royal Navy eventually ground the Chinese into submission, forcing on them the Treaty of Nanking, opening of trade along with continuance of the opium trade, compensation, and the ceding of Hong Kong to the British. Young points out that ‘The history of past commerce with that country, will, it is believed, demonstrate the fatal consequences of the system in which it has been generally conducted, and the necessity for guiding it in future on totally different principles.’ The central principle of his argument is that of ‘the impolicy of giving a political character to our future relations with China.’ Perhaps he has New Zealand in mind, with his father a major player in the New Zealand Company, where British politics were always running behind the more adventurous, theory-driven, immigration activities of the Company. But then China was about trade. His plan was to abandon Canton, with all its complications, and set up a chain of depots or entrepôts on islands in the Eastern and Yellow Seas, out of reach presumably of the Chinese Court, and able to face the growing competition of Russia and America.

While he might criticise British policy, however, he was still a cheerleader for the Empire. ‘God forbid that the fortunes of England should yet be waning, and that the historian should hereafter date from the commencement of this unjust war the commencement of the Decline and Fall of the British Empire!’ He is clear on his views of the emerging war, ‘this shameful struggle’ and alas unwillingly predicts exactly what happened in its aftermath over the next decades ‘lest we bring on our country a lasting infamy, dishonouring the flag of England, dimming the lustre of her arms, exposing her honour to reproach, and her noble name to scorn.’

Young’s book was based on an article he first published in the Colonial Gazette[4]. He has done his reading, and quotes recognised authorities from the 17th to 19th centuries including De Guignes, Kircher, Nieuhof, Morrison, Staunton’s Penal code, Timkowski, Davis, and others. The Chapters are on the Chinese races, treaties, history, the future, facts, opinions which includes a series of quotes for noted writers on China, and a final chapter on war or peace. Here he doesn’t hold back. ‘China, it seems, has offered to England the two deepest affronts that a weak nation can put upon a strong one. She has mocked ger power, and exposed her to just obloquy. No hope, then, of terms until the insult is washed out in blood. By our own act and deed, we place ourselves within the pale of foreign laws: we break them without fear or scruple: and when we are made to feel their authority, we bitterly complain of so great an outrage……’ And so he goes on: ‘We entered China, not no the invitation of a hospitable people, not by their wish, scarcely by their consent, but in spite of their opposition – ….. Having achieved a position in China, ‘and at length fairy seated ourselves within the pale of these very laws we had been so resolute in opposing…..Had we been content this, all would have been well.’ But of course, the British soon put themselves beyond the pale, not prepared to bow to the ‘laws which kept us in our factory like wild beasts in a cage..’ Instead of war, which was just developing as the book was published, the British should withdraw to off-shore islands and get on with their trade. How the Americans, French and Russians would have been rubbing their hands as they filled the vacuum. The history of 19th C imperial trade shows that if you were not in the middle of things scrapping with competitors and capturing local authority, then you could be safely ignored.

It is the polemic of a young man, caught between imperial adventure and trade, and an insight into injustices, not unfamiliar to us here in New Zealand today.

[1] Burns, P., Fatal Success. A history of the New Zealand Company. Auckland, Heinemann Reed, 1989. pp 129-130.

[2] https://www.thecurlingfamily.com/curling-and-youngs-shipyard.html

[3] https://cristinasanders.me/2019/02/13/william-curling-young/

[4] The Colonial Gazette,, No 49, October 30, 1839. This independent journal was published weekly under the auspices of the Colonial Society of London, from the offices of the Spectator, targeted at a colonial readership.

21st Feb 2023 - Rare and Early Books

Early books on China: Much of the literature of western accounts of travel to China focuses on the route from

1st Nov 2024 - Rare and Early Books

Another mid-19th C life of adventure. Naturalist on Beechey’s three year pacific voyage, aimed at meeting up with Franklin when