Smallpox vaccination at the edges of the Empire

24th Jun 2024 - Blog

When you read old books, you often come across things that have a strong connectivity. Often what seems to be

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, going to prison, if you had some means, was not necessarily the end of the world. Not far off it perhaps, but you could make yourself comfortable, and even do something useful. In 1813, Leigh Hunt the editor, critic, poet and always at the centre of the romantic literary movement, was imprisoned for 2 years for seditious libel of the Prince Regent. He eventually had a room in the prison which he decorated and furnished, with access to a garden, and developed a literary salon there, with visits by notables such as Charles Lamb, William Hazlitt, Jeremy Bentham, and Lord Byron. He continued his writing, including editing The Examiner. Later in the century in 1827, Edward Gibbon Wakefield, was imprisoned for 3 years for abducting a young woman, and in Newgate managed to tutor his two sons, write some articles on emigration, and develop his theories on colonisation and emigration policy.

The last decade of the 18th C was even more hazardous for writers criticising the Government, supporting the ideas of the French revolution, or in the case of the Wordsworths and their friend Samuel Coleridge, even walking in the night across the Somerset countryside (they were suspected of being French spies). The Pitt Government brought in drastic legislation against sedition, treason and libel and writers spoke out at their peril. A minor character in the turmoil of the time was William Winterbotham (1773-1829).

Winterbotham was baptised at Old Ford[1] and took up the Baptist ministry in 1789. Three years later, on the 5th and 18th November 1792, he gave two sermons, referring to the French Revolution and calling for civil and religious liberty. Comparatively tame stuff, but he was arrested and on consecutive days, in jury trials on 25 and 26 July in Exeter, was convicted of sedition for his radical views and imprisoned for four years, and fined £100 for each sermon.[2] Winterbotham used his time well, profiting from his acquaintance with a fellow prisoner in Newgate, the radical publisher and printer James Ridgway. Ridgway (1782-1838) had been imprisoned in May 1793 for four years and also fined £200, for printing Thomas Paine’s ‘Letter addressed to the Addressers’, part II of his ‘Rights of Man’, and Charles Pigott’s equally radical ‘The Jockey Club’.[3]

Winterbotham was baptised at Old Ford[1] and took up the Baptist ministry in 1789. Three years later, on the 5th and 18th November 1792, he gave two sermons, referring to the French Revolution and calling for civil and religious liberty. Comparatively tame stuff, but he was arrested and on consecutive days, in jury trials on 25 and 26 July in Exeter, was convicted of sedition for his radical views and imprisoned for four years, and fined £100 for each sermon.[2] Winterbotham used his time well, profiting from his acquaintance with a fellow prisoner in Newgate, the radical publisher and printer James Ridgway. Ridgway (1782-1838) had been imprisoned in May 1793 for four years and also fined £200, for printing Thomas Paine’s ‘Letter addressed to the Addressers’, part II of his ‘Rights of Man’, and Charles Pigott’s equally radical ‘The Jockey Club’.[3]

[Rev. William Winterbotham. Oil painting by John Ponsford of Devon, depicting Winterbotham in 1828, a year before he died.]

In prison, obviously with time on his hands, Winterbotham wrote his account of China.

Winterbotham, W. An Historical, Geographical and Philosophical View of the Chinese Empire, Comprehending a Description of the Fifteen Provinces of China, Chinese Tartary, Tributary States; Natural History of China; Government, Religion, Laws, Manners and customs, Literature, Arts, Sciences, Manufactures, etc. to which is added, a Compendious Account of Lord Macartney’s Embassy, compiled from original communications. London, Ridgway and Bottom, 1795. [10], 435, 114 pp, 6 engravings, map. Cordier 2392; Lust 79, 80.

It is based on the first book published on the famous Macartney embassy to Peking of 1792-44, by Aeneas Anderson, valet to Lord Macartney, who jumped the gun, getting his account out in 1795, two years after the Embassy returned and two years before the official account published by George Staunton in 1797. There was much speculation about how much was written by Anderson and how much by the bookseller and journalist Ebenezer Coombes, of Coombs and Bishop in the Strand. Winterbotham and Ridgway must have had access to Anderson’s manuscript. This rapid publication was in response to the great public interest in the Macartney embassy, particularly with a view to its perceived political and diplomatic failure. Hence the famous lines in it describing the embassy: ‘We entered Peking like paupers; we remained in it like prisoners; and we quitted it like vagrants.’ The book was later dismissed by John Barrow, the second secretary on the mission, writing in his own 1804 account: ‘A book that was published in the name of one Aeneas Anderson, who was a livery servant of Lord Macartney, but which in fact was a work vamped up by a London bookseller as a speculation that could not fail, so greatly excited was public curiosity at the return of the Embassy.’

Winterbotham doesn’t name Anderson, but says in his preface: ‘The Editor has only to add, that in compiling this work, he as investigated different accounts with impartiality, stripping the accounts of visionary missionaries of their of their absurdities; and by collecting the facts respecting, the natural history population, government, laws customs, religion, literature, sciences, manufactures, etc, of the Chinese empire, he hopes he has enabled the reader to form a pretty correct opinion of the nation, in many instances the most astonishing of any recorded in the pages of history.’ And then ‘With respect to the account of the Embassy, he has only to say, the materials from which it was compiled, were furnished to the publisher by one who formed part of the suite attendant on the Embassy, and has every proof that the author was an attentive observer.’ Most of the book comprises a number of chapters on a general description of China, a description of the Empire, Tartary and tributary states, natural history, manners and customs, the population, religion arts and sciences. This all must come from a variety of sources. It is followed by the account of the embassy. Writer and publisher not only accessed Anderson’s account, but pulled together a variety of plates and a folding map ‘laid down from the Jesuits maps, made from actual surveys, and includes the whole of China, Chinese Tartary and the tributary kingdoms.’ There are seven plates: standard and warlike instruments; dresses; ornaments on the dresses; the Emperor in his carriage of ceremony; Observatory of Pekin (folding); two plates of instruments of music. The engraving of the Emperor in his carriage[4] first appeared in a work by the French Jesuit De Mailla, not published until 1777, long after his death,[5] when the work was rediscovered by Jean-Baptiste Grosier and Michel-Ange-André Le Roux Deshauterayes. It was re-used by Grosier in 1787[6], which is the likely source. The Pekin Observatory, showing that established by the Jesuit Ferdinand Verbiest, is from the well-known original engraving published by the French Jesuit priest Louis Le Comte, in 1697. The effort all seemed worthwhile, particularly with the official account still a couple of years off, and two editions were issued in 1795, and an American one in two volumes, without map or plates, in 1797.

rediscovered by Jean-Baptiste Grosier and Michel-Ange-André Le Roux Deshauterayes. It was re-used by Grosier in 1787[6], which is the likely source. The Pekin Observatory, showing that established by the Jesuit Ferdinand Verbiest, is from the well-known original engraving published by the French Jesuit priest Louis Le Comte, in 1697. The effort all seemed worthwhile, particularly with the official account still a couple of years off, and two editions were issued in 1795, and an American one in two volumes, without map or plates, in 1797.

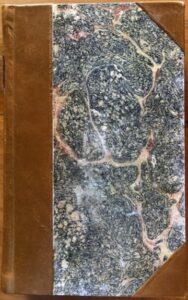

Winterbotham’s book is very hard to come by, and my copy is the second edition iss ued in the same year as the first. The covers and spine were in bad shape, and The Bookbindery in Mt Roskill, Auckland, did a very fine job re-casing it, cleverly making a copy of the original marble paper on the boards and using that on the new boards, along with a new spine.

ued in the same year as the first. The covers and spine were in bad shape, and The Bookbindery in Mt Roskill, Auckland, did a very fine job re-casing it, cleverly making a copy of the original marble paper on the boards and using that on the new boards, along with a new spine.

The other profitable project by Winterbotham and Ridgway started in prison was a four volume history of America, also published in 1795[7], with an American edition in 1796. This again was assembled from a range of published sources, but in all, not bad going for a couple of years’ work, even with enforced idleness available. He was released in 1797, married a Mary Brend, and making up for lost time, produced seven children before dying in Stroud in 1829.

[1] The crossing of the River Lea, now in the midst of the borough of Tower Hamlets in London,

[2] Susan J. Mills, “Winterbotham, William (1763–1829)”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 (http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/29771)

[3] https://radicaltranslations.org/database/agents/2325/; Pigott, Charles, The Jockey Club, or a Sketch of the Manners of the Age. London, H B Symonds, 1872.

[4] https://www.bgc.bard.edu/research-forum/articles/184/the-emperor-in-his-ceremonial

[5] Mailla, J de Moyriac de, Histoire generale de la Chine, ou annales de cet Empire, traduites de Tong-Kien-Kang-Mou. Publisees par M. l’Abbe Grosier, et dirigees par M. Le Roux des Hautesrayes. Paris, Chez Pierres. Clousier. MDCCLXXVII.

[6] Groser, J., Description generale de la Chine contenant. Paris, chez Moutard, MDCCLXXXVII.

[7] Winterbotham W., An Historical Geographical, Commercial, and Philosophical View of the American United States, and of the European Settlements in America and the West-Indies. Published by London For the Editor; J. Ridgway, H.D. Symonds, et al. 1795.

24th Jun 2024 - Blog

When you read old books, you often come across things that have a strong connectivity. Often what seems to be

1st Mar 2025 - Blog

Unopened, uncut, half cut, and a butterknife ‘To introduce Wordsworth into one’s library is like letting a bear into a